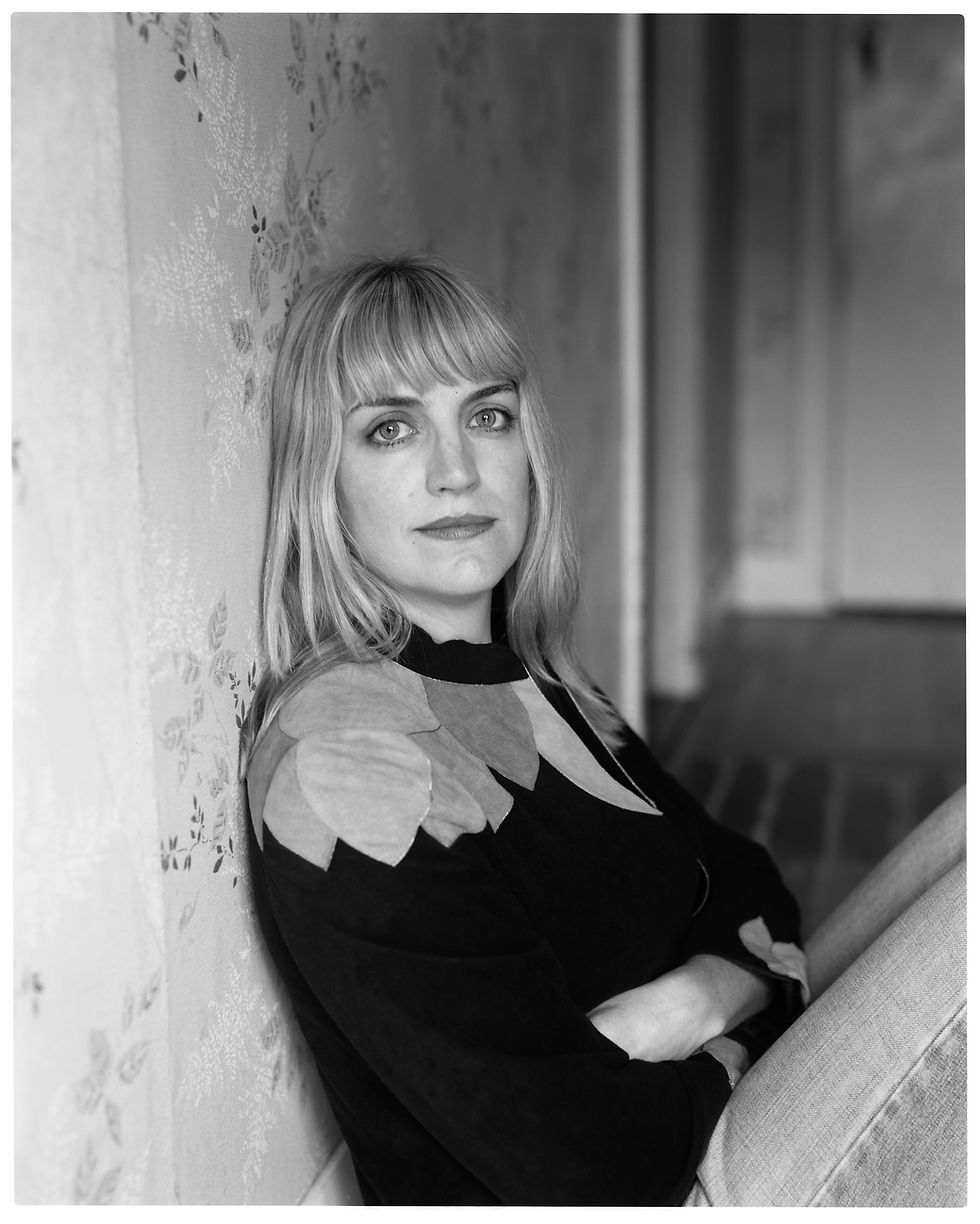

TO ERR IS HUMAN, TO FORGIVE …: THE BRANDI CARLILE INTERVIEW part 3

- Mar 13, 2020

- 4 min read

Can you believe and trust when that belief can be spat back in your face? Can you say, as Brandi Carlile once sang, “you can't take back what you have done/You gotta keep your heart young”?

Concluding this three-part interview, thoughts turn to not just doing good and being good – which in many ways we covered in the first two parts HERE and HERE – but to what to do when you, and especially the world, does not do right.

The answer may be give peace – and love and understanding - a chance.

The essence of Brandi Carlile’s Grammy winning 2017 album, By The Way I Forgive You, was as it says on the tin, forgiveness. Which sounds wholesome, good and something no one would object to, right?

Except of course that it’s not always something that is easy to explain or understand once you get past the Hallmark moment.

Some people resist forgiveness because they think it means allowing someone to get away with doing harm. Some people dive into it because they think it will heal them to do it, as many self-help books like to say.

Some of us though, see either of those choices as maybe a little too easy, too simplistic. So, Brandi Carlile, what does forgiveness mean to you?

“Well, there’s another interpretation which is even more disturbing,” she says, pointing at the “little problem with sanctimony and patronising” that the US has, that expectation of being forgiven.

“I’m not preaching when I talk about [forgiveness]. It’s something even I struggle with on a daily basis: forgiving others, forgiving things in my past, forgiving the things that I know are about to happen in my future like losing a parent and struggles with our health. And also forgiving myself: I do Catholic guilt in a big way.”

Ah, now we’re talking. Catholic guilt – mother’s milk to some of us. But we’re not yet any closer to a definition, if there is one readily available.

Remember, as we saw in the first part of this interview, we’re talking someone whose existence as a lesbian was long judged anathema in the musical, let alone social and political circles, she worked in. Someone who secretly married her partner, Catherine – with whom she has two daughters - before the law was changed in the USA to recognise that union.

“It’s just a radical, ugly, global concept and that word here has become a very white, middle-class, Judaeo-Christian, “#blessed” word and I’m fascinated by the divide between how radical the concept actually is and how homogenised our understanding of it is,” says Carlile, who then reveals a rather radical, you might even say brave, approach to the hoary concept.

“I’ve asked for it before people knew what I did was wrong. That seemed more important than what I was asking for: me letting them know that I know I have hurt them. That can do healing, that can do things for people’s souls that they might not even know they needed. And I know I need it.

“I need that kind of acknowledgement from other people. As soon as I know somebody knows they’ve wronged me and that they wish they hadn’t, it’s like it never happened. I think I admire them more than if I had never been hurt.”

This isn’t idle thought or even flaky self-actualisation but something learned before even understanding it. Something that is as simple as faith. So, does faith still play an important role for her?

“Oh yeah, a very, very important role. I’m the rejected progressive reformist student of the Bible as a historical document. You could call me Christian but I don’t really need that word.”

When Carlile says rejected, it is quite literal: as a teenager she was refused baptism by her local minister, in front of the congregation, because she had already come out.

“I had my swimsuit on under my clothes, they’d invited my family and friends – everyone,” she told The Guardian last year “That’s when they decided to make an example of me. I’d been on a lot of stages in my life, but that was an irreversibly damaging public humiliation.”

She has said that that rejection has never left her mind, which raises this thought, does she not belong to things now because it means that she won’t be rejected, choosing to build a belief system around herself and her life?

“No I still go back to the well, and I’m proud to and happy to.” Carlile says. “I react to that initial rejection all the time in my life, it’s probably one of my greatest gifts and platforms. But people who are rejected by the basic tenets of faith, and let’s say for the sake of discussion it’s the Christian faith, tend to be closer to understanding it than people who aren’t.

“I’ve really been fascinated by that juxtaposition most of my adult life and it has made me a person of an even stronger and more poignant faith. I’m practising and I’ve been able to bring that to my children and it’s an important part of my life.”

And that includes, yes, forgiveness.

Brandi Carlile will play Hamer Hall, Melbourne, April 6; Enmore Theatre, Sydney, April 8; and Bluesfest, Byron Bay, April 9-14.

Comments